The Royal Festival Hall organ: a short history

William McVicker, curator of our Royal Festival Hall organ, looks back across the instrument’s history as we celebrate its 70th anniversary.

When the details of a proposed new organ for the Royal Festival Hall were first published, letters of criticism appeared in the pages of newspapers and music journals before a note had even been heard. In an article in The Times in March 1954, days before the opening, ‘Our Music Critic’ predicted that the ‘tax-payer’s organ’ would introduce a repertoire of strange new words; of ‘mixture’, ‘mutation’, ‘harmonics’, ‘partials’. He went on to say that ‘it may be well – before any of us say how much we like or dislike this large, expensive new instrument – to sort out the issues.’

Seventy years on, and not only are those ‘issues’ not as contentious as once considered, but this important instrument caused a reassessment of English organ design, and had a far-reaching impact on organ-building culture. But how was it that the project consultant and Royal Festival Hall’s first Organ Curator Ralph Downes (pictured above), and the organ’s builders, Harrison & Harrison of Durham, came to produce such a radical organ?

Background and influences

At the beginning of the 20th century, the great Alsatian organist and musicologist Albert Schweitzer had asked far-reaching questions concerning the state of organ-building practice in Europe. His research gave rise to a 1926 conference in Freiburg which sought to re-establish the construction principles of good ‘classical’ instruments. The conference led organ builders to attempt to copy the sounds of earlier 17th and 19th century instruments, in a German organ revival movement that became known as the Orgelbewegung.

The seeds of Orgelbewegung soon spread to America and it was there that this burgeoning organ-building philosophy, and its ideas around historical performance practice, were first encountered by Downes, who was then employed as musical director and organist at Princeton University. On his return to England, Downes became resident organist for the London Philharmonic Orchestra, and in 1948 was commissioned by the London County Council to design an instrument for the Royal Festival Hall.

From the outset Downes, leaning on the principles of Orgelbewegung, sought to build an instrument which returned to the tonal design principles that could do justice to the contrapuntal music of Johann Sebastian Bach and his contemporaries. In order to do this, he sought characterful organ sonorities and architectural choruses of ‘clean’ sound, capped by what are known as brilliant ‘mixture’ stops – a characteristic loosely termed ‘continental’ or ‘Baroque’.

Channelling the spirit of the Festival of Britain

Our Royal Festival Hall had opened in 1951 as part of the Festival of Britain site on London’s South Bank. The revolutionary thinking of the festival promised revitalisation for post-war Britain, where everything was to be new; it represented the future through invention, colour and excitement. A ‘beacon for change’ the Festival of Britain embraced a spirit of imagination and adventure which would be wholly reflected in Downes’ thinking.

The inquisitive architectural spirit of the age, evident in the design of the Royal Festival Hall, owed much to continental influences – both Italian and Scandinavian. And in keeping with this the Royal Festival Hall organ’s concept and construction would also accord with the ideals of the Festival. In Downes’s own words, the instrument was built ‘to embody excellence in quality of materials, workmanship [and] artistry.’

Encountering resistance

Downes’ ideas were not universally popular among the musical establishment. He had the support of leading figures including composer Benjamin Britten; Royal Philharmonic Orchestra founder Sir Thomas Beecham; Professor of Music at the University of Oxford, Sir Jack Westrup; and G Donald Harrison, an English organ-builder who championed the ‘American Classic’ organ. But he also faced opposition, notably from director of the Royal College of Music, Sir George Dyson; president of the Royal College of Organists, Sir George Thalben-Ball; chief conductor of the Proms, Sir Malcolm Sargent; and the composer Dr Ralph Vaughan Williams. Their objections were chiefly focused on the design’s ‘continental’ or ‘Baroque’ influence – a concept so evidently abhorrent to Ralph Vaughan Williams, he felt compelled to write a letter to The Times in 1951.

‘I admit that we have some bad organs in Britain, but at their worst they cannot surely make so nasty a noise as those on the continent.’

It was agreed that these objections were chiefly due to differences in taste and though slightly modified and adopted, Downes’ scheme would be built. Tasked with constructing the instrument to his ground-breaking specification were Harrison & Harrison Ltd of Durham. Downes’ design required the firm to construct pipework in a style virtually unknown in England. Yet although the processes for the voicing of the pipes – the so-called ‘open-foot’ technique – were new to Harrison & Harrison, they stuck religiously to Downes’ ideas.

The Royal Festival Hall instrument thus occupies a pivotal position in the history of the English organ. In effect the first ‘neoclassical’ British organ to reflect a desire to serve a wide range of earlier keyboard repertoires, its construction heralded the arrival of the Organ Reform Movement in England.

Appearance and initial reaction

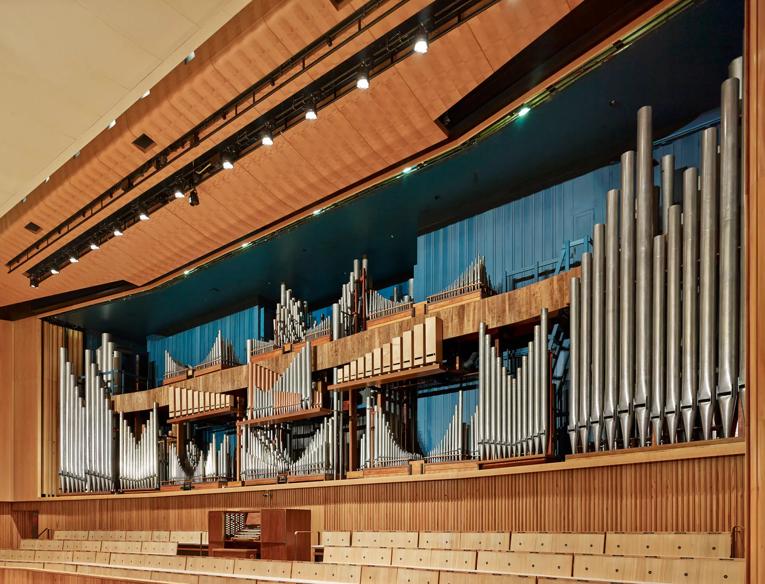

How the organ would look was a further source of debate throughout its planning. Some felt that a ‘town hall’ symmetrical array of large organ pipes would be appropriate, whilst others thought a grille covering the entire opening (as was common of cinema organs of the time) would suffice. The deadlock was ultimately resolved by the leader of London County Council and Chairman of the South Bank Committee, Isaac Haywood. ‘We are paying for all these expensive pipes and we want to see them as a decorative feature of the hall,’ he said. And with that the organ’s internal layout, which had initially assumed to be hidden from view, became the exposed pipework we see today. Its appearance stunned audiences at the time, but the organ’s open-plan character would prove the jewel in the crown of the hall’s architecture, offering a striking backdrop for the world’s great orchestras.

The official opening for the Downes designed Harrison & Harrison organ was 24 March 1954, with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Sir Adrian Boult, performing a programme of works with Downes and André Marchal as soloists. This was followed, on 27 March, by a recital from four of the most celebrated organists of the day: Downes, Arnold Richardson, Lady Susi Jeans and Sir George Thalben-Ball. Reporting on the opening performances The Daily Mail wrote of ‘a brilliant concert instrument worth all the £51,000 the LCC has paid for it’ and ‘a night of triumph for Mr Downes’.

Notable performances

Over its seven decades, the Royal Festival Hall organ has regularly hosted the greatest players of the day, including French legends Marcel Dupré and Maurice Duruflé, Italian virtuoso Fernando Germani, Dutch conductor and musicologist Ton Koopman, as well as a long list of famous English organists, including William Lloyd-Webber, Peter Hurford, Dame Gillian Weir and Simon Preston. Many new organ works have been written for, and played on, the Royal Festival Hall organ, with Britten asked to write an organ concerto for the instrument – but he never completed the commission.

Beneath the organ’s stops is a plaque which reads ‘Definitely No Smoking at the Console’; it’s suggested it was added due to the great Parisian organist Pierre Cochereau – one of the first visitors to the organ in 1956 – who was known to have a propensity for stubbing out his Galouises on the console of the instrument in Notre Dame Cathedral. On 3 March 1971, during a performance of Ligeti’s Volumina, organist Xavier Darasse managed to break the instrument. A note on the timed copy of the programme states ‘the last work was not played, as the organ fused after the first chord’.

Restoration and refurbishment

The only significant break in the Royal Festival Hall organ’s musical life to date came after half a century in service, when the Royal Festival Hall underwent refurbishment work between 2005 and 2007. A much needed improvement in the hall’s acoustics was the catalyst for the works, which included an enlargement of the stage and, to accommodate this, a reduction to the depth of the organ. This necessitated a complete remodelling of the instrument’s structure, without sacrificing its tonal design and musical style. A complex project, for which Harrison & Harrison returned to the Southbank Centre.

One of the most challenging aspects of the organ’s restoration was its visual appearance, with Harrison & Harrison needing to retain the principles of the instrument’s original design, whilst also adapting to new audience sightlines opened up by the acoustic remodelling of the auditorium. Of the changes most visible from the hall’s seats are a rearrangement of the organ’s largest 32ft pipes, whose original disorganised appearance had been described as a ‘jumble of stalks in a jar’. These pipes, at the organ’s extreme ends, are now arranged in a more formal manner, with a new arrangement of 16ft principal pipes in front of them, to offer a greater visual balance. The organ has also retained its monogrammed frontispiece – added by the hall’s deputy architect, Sir Leslie Martin – but only just. As this frontispiece is purely aesthetical – consisting of dummy pipes – it was originally set to be scrapped, owing to the lessened space. But, as it had become a much-recognised aspect of the organ second thoughts prevailed, and a shallower reproduction can be seen in situ.

Other less visually obvious work done during this time included a rethinking of the organ’s interior layout and pipework to make better use of space within its reduced depth. The organ’s console was attached to its main structure; new quieter electric slider-actions replaced the original mechanisms; the organ’s key transmission, electronic coupler and combination systems were replaced, and three new soundboards were constructed. And there was the not insignificant task of a full overhaul of each of the 26 double-rise reservoirs (the organ’s lungs) and all 7,866 pipes.

Having been removed from the hall for the duration of refurbishments, one third of the organ was reinstated for the hall’s reopening in 2007, with the remainder finally back in situ and in full working order in 2014. Since then, benefitting a much more favourable acoustic – particularly in its lowest notes – our much-loved organ has soon re-established itself as an integral part of one of the world’s leading concert venues.