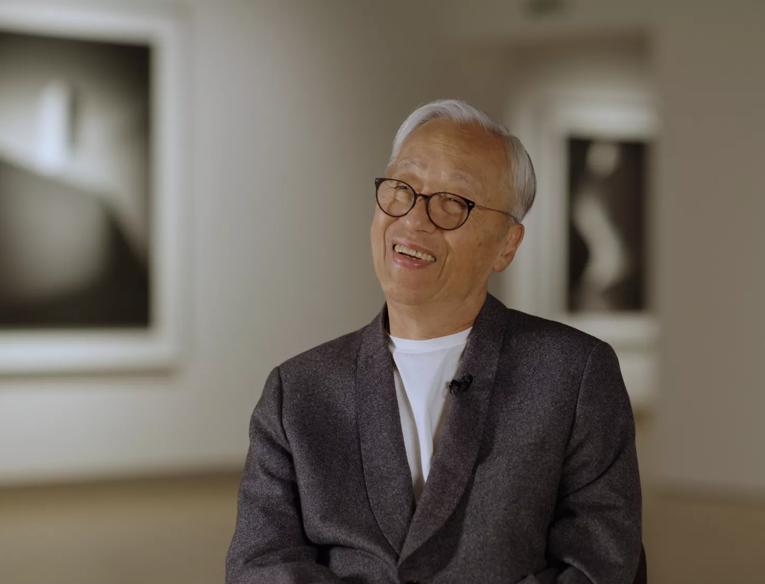

Hiroshi Sugimoto: formative years and significant works

For five decades the work of photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto has received international acclaim, whilst being presented in major galleries and institutions the world over.

Sugimoto’s photographs are meticulously crafted, often stretching and rearranging the concept of time, and our understanding of the world around us, and he has often re-explored ideas and practices from photography’s earliest exponents. Over the past 50 years, he has often revisited and expanded upon his own ideas, and series, which we take a closer look at, along with the artist’s formative years, here.

Hiroshi Sugimito: early years

Hiroshi Sugimoto was born in Tokyo in 1948 to a family of merchants. Among the young Sugimoto’s interests were trains, electronics, carpentry and photography, with his early fascination with the latter further enhanced by one of his elementary school science teachers, who showed Sugimoto and his classmates how to use photosensitive paper to make photograms. ‘He used spoons and forks and other items and he exposed the paper under the light for five or six minutes.’ explained Sugimoto, looking back. ‘When he removed it, the shapes of the spoons and forks remained on the paper. It was an amazing experience for me that left a lasting impression’.

At the age of 12 Sugimoto was given his first camera, a Mamiya 6 medium-format, by his father, which he would use to take photographs of trains and gather reference material for model-making. When he moved on to high school, Sugimoto joined the photography club and also began developing an interest in the cinema, which he would visit regularly. It wasn’t long before his love of film and photography combined, as he recalls, ‘Audrey Hepburn was beautiful and I fell in love with her on the screen. I wanted her portrait so I brought my Minolta SR7 camera into a movie theatre, and I studied how to stop the image on the screen. I found that one-fifteenth and one-thirteenth of a second stops the image’.

In 1970, after graduating in Economics from Tokyo’s Rikkyo University, Sugimoto backpacked across Russia and Europe. Influenced by communist ideology, and the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels as a student, he had wanted to experience Russian society, but disillusioned by what he found, he duly continued on to Europe. ‘I kept moving westwards. I stayed in Moscow for a few weeks and took another train to Poland, and then to Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria and other Eastern European countries. After several weeks I arrived in Vienna for my first taste of Western civilization’.

Hiroshi Sugimoto in America

Later in 1970 Sugimoto would get another taste of Western civilization as he travelled to the US, and California. Here he studied at Los Angeles’ ArtCentre College of Design, specialising in photography. Speaking of his studies here, Sugimoto has said ‘ArtCenter College was more like a training school for technicians: car design and advertising. For photography you trained to be a commercial photographer, which is what I wanted. I wasn’t interested in academic study at all’.

After completing his study in Los Angeles Sugimoto moved to New York in 1974 in order to pursue a full-time career in photography. Here, Sugimoto soon became part of the city’s hippy counter-culture.‘I got serious about using photography as a tool in my art after I moved to New York’, says Sugimoto. ‘I saw many good shows, mainly minimalist shows: Sol LeWitt, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd. When I moved to the East Coast I found so many interesting people that I decided to stay. I’d just finished my photographic studies and was hungry to work. Since photography was considered a second-class citizen in the art world then why not use photography? It was more interesting for me to start with something a step down and bring it up’.

Dioramas

In 1974, Sugimoto made his first visit to the American Museum of Natural History in New York, it was a visit that would inspire his first major breakthrough in photography. ‘I made a curious discovery while at the exhibition of animal dioramas,’ the artist explains. ‘The stuffed animals positioned before painted backdrops looked utterly fake, yet by taking a quick peek with one eye closed, all perspective vanished, and suddenly they looked very real. I had found a way to see the world as a camera does. However fake the subject, once photographed, it’s as good as real’.

Inspired by these taxidermy dioramas, he went on to commence his Dioramas series, which among its initial works included Polar Bear (1976) and Hyena - Jackal - Vulture (1976). Sugimoto would return to this idea two decades on, adding more works to Dioramas in the 1990s including 1994’s Earliest Human Relatives. In 1978 Polar Bear was acquired by The Museum of Modern Art, representing Sugimoto’s first photographic sale. The work was also exhibited in the museum’s Recent Acquisitions show, that same year.

Theaters

It was whilst working on his Dioramas series, that Sugimoto also found the inspiration for his next series, Theaters, as he would later detail. ‘I am a habitual self-interlocutor. One evening while taking photographs at the American Museum of Natural History, I had a near-hallucinatory vision. My internal question-and-answer session leading up to this vision went something like this: ‘Suppose you shoot a whole movie in a single frame?’ The answer: ‘You get a shining screen.’ Immediately I began experimenting in order to realise this vision’.

He began this series in 1976, by photographing St. Marks Cinema in Manhattan’s East Village, and the first group of works would also see Sugimoto capture other movie theatres and cinemas in the Northeast and Midwest of the US. It was an approach that the photographer has returned to again and again over the course of his career, firstly in 1993 when he broadened the Theaters series to include depictions of Drive-Ins across the US. The photographer later travelled to Europe, primarily Italy, to replicate the approach with Opera Houses in 2014, and then in 2015 began photographing Abandoned Theaters.

Seascapes

The seeds for Sugimoto’s Seascapes series were sown in 1980. ‘One New York night, during another of my internal question-and-answer sessions I pictured two great mountains’, the photographer has explained. ‘One, today’s Mount Fuji, and the other, Mount Hakone in the days before its summit collapsed, creating the Ashinoko crater lake. When hiking up from the foothills of Hakone, one would see a second freestanding peak as tall as Mount Fuji. Two rivals in height – what a magnificent sight that must have been! Unfortunately, the topography has changed. Although the land is forever changing its form, the sea, I thought, is immutable. Thus began my travels back through time to the ancient seas of the world’.

Sugimoto began the series that same year with a photograph of the Caribbean Sea, taken from a bluff in Jamaica while on a family holiday to the island. Seascapes would subsequently lead Sugimoto across the globe, photographing bodies of water from the Ligurian Sea viewed from Italy to the North Pacific Ocean viewed from Japan.

Chamber of Horrors and Portraits

In 1994 Sugimoto made his first visit to Madame Tussaud’s in London, where he photographed his Chamber of Horrors series on location. ‘I saw the blade that guillotined Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, and the electric chair that executed the Lindbergh baby’s kidnapper, among other exhibits. They all looked very real to me’, Sugimoto said. ‘To corroborate these various murderous instruments invented by civilised men, I took the requisite eye-witness photographs: thus did people in times past face death head on’.

Sugimoto would return to the wax museum five years later to photograph his Portraits series, for which he was given special permission to remove selected figures from the display to photograph individually, among them Diana, Princess of Wales (1999), Fidel Castro (1999) and Anne of Cleeves (1999). However, he found that the exhibits he had previously captured for Chamber of Horrors had now been removed from the museum. ‘When I asked why,’ he said ‘I was told they’d been removed in a gesture to political correctness. Must we moderns be so sheltered from death?’

Opticks

In 2018 Sugimoto began printing his Opticks series, which was inspired by an 1704 work of the same name by Isaac Newton, in which Newton, through his experiments with prisms presented proof that natural light was not purely white. Drawing on Newton’s approach, Sugimoto used a batch of Polaroid film he had been gifted – one of the last batches of film Polaroid ever produced – along with a glass prism and a mirror to create condensed vivid compositions of pure colour. Sugimoto then enlarged these works into chromogenic prints. Opticks was presented for the first time in 2020 at the Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art in Japan, and received its first UK presentation here at the Hayward Gallery.

The largest survey to date of Hiroshi Sugimoto’s work was at Hayward Gallery, 11 October 2023 – 7 January 2024. Enjoy more articles and videos connected to this exhibition, below.

From internationally acclaimed artists at Hayward Gallery, to pop-up installations, enjoy inspirational art and exhibitions with us.